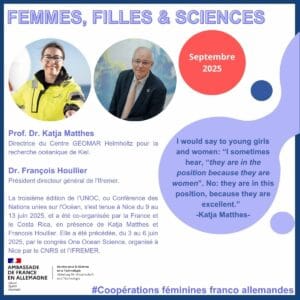

Série Femmes, filles et sciences #9 – septembre 2025

Le Service pour la science et la technologie de l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne met en lumière des femmes scientifiques et des managers de projets, en particulier des coopérations franco-allemandes scientifiques féminines, contribuant ainsi à la déclinaison par l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne de la stratégie internationale de la France pour une diplomatie féministe (2025-2030). Plus d’informations : https://de.ambafrance.org/Strategie-internationale-de-la-France-pour-une-diplomatie-feministe-2025-2030

Prof. Dr. Katja Matthes est directrice du Centre GEOMAR Helmholtz pour la recherche océanique de Kiel (https://www.geomar.de/en/) et professeure de physique de l’atmosphère. Dr. François Houllier est président directeur général de l’Ifremer (https://www.ifremer.fr/fr). Il est polytechnicien et docteur en biométrie forestière.

La troisième édition de l’UNOC, ou Conférence des Nations unies sur l’Océan, s’est tenue à Nice du 9 au 13 juin 2025, co-organisée par la France et le Costa Rica (https://unocnice2025.org/). Dans ce cadre, le congrès One Ocean Science, organisé par le CNRS et l’IFREMER, a eu lieu du 3 au 6 juin 2025 à Nice (https://one-ocean-science-2025.org/).

What brought you to science, to your fields of research and to the topic of the ocean?

Katja Matthes: I decided studying meteorology towards the end of high school. I loved mathematics and geography, and meteorology combined both fields. I visited the Institute for Meteorology in Berlin and decided that this was the topic I would like to study. And early on, I was also very keen on working in research. I really wanted to understand climate change and contribute to this subject. During my PhD, I studied natural climate variabilities on a 10-year time scale, on which the ocean plays a major role. I first did models only with the atmosphere, but then realized that the ocean is very important and I put both together. I continued this work as a fellow at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder/USA and Japan and during my first postdoc positions in Germany. bevor I joined GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel as a professor. Then, almost six years ago, I was asked to lead the center.

Francois Houllier: I am an engineer by training. At the end of my studies as an engineer, I had the opportunity to make a PhD, which was normally not the expected career after my engineer school, I should have become someone working in the French Administration. But I decided to go for science by curiosity. I was trained in mathematics and physics, and was interested in forest biometrics. I was involved in the National Forest Inventory Service in France, and after that, I spent some time working with National Forest Inventory and teaching forest biometrics. I had the opportunity to spend a few years in India, where I was exposed to a diversity of disciplines, from social sciences to forest ecology. I continued in the area of forest ecology, plant ecology, plant modeling. After that, I ran the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) from 2012 to 2016 and later I was involved in a cluster of universities in Paris (Université Sorbonne Paris Cité (USPC)). When the opportunity appeared to become the President and CEO of IFREMER, I applied for it.

I had no previous strong exposure to ocean science, but a few things. For example, when you look at forest demographics, you use models that are similar to those you are using in fish population dynamics. Also, when I was working in forestry, I had the opportunity to be a member of a commission at CNRS in France, which evaluated research labs, including the marine research stations. And, when we created the Department of Ecology at INRA, the National Institute for Agricultural Research, it was a Department of Ecology for Forest, Grasslands, and Freshwater. Those working on freshwater, they were working on lakes, and they were inspired, by what has been done in the ocean, because there are some similarities between the ocean and the lakes, for example in terms of microbial functioning. So, I had some small exposures to ocean science. And since nearly seven years now, I have been chairing IFREMER, and I am very happy with that.

Why was the topic of ocean interesting for you as researchers?

Katja Matthes: The ocean covers 70% the Earth’s surface. You cannot talk about climate or climate change without the ocean. Now being a director offers me the opportunity to contribute to the solution of the grand challenges we have. I love guiding the center and at the interface between science and politics. This is what we also did at UNOC in Nice, where we went into the dialogue between science, politics and NGOs to really push the global transformation that we need in order to reach the climate goals and move towards climate neutrality. For a few years now, the ocean has been on the international agenda of climate politics, and this is very important. Finding solutions to the climate crisis is crucial, and the ocean offers a number of them. What unites GEOOMAR and IFREMER is that we both do research on ocean-based solutions to societal challenges. At GEOMAR, one focus is to investigate different, marine carbon sinks, such as sea grass meadows, mangroves, ocean alkalinization or CCS [Carbon Capture and Storage]. These are important in terms of decarbonization. This is why ocean research plays a vital role.

Francois Houllier: I don’t remember exactly what moved me when I applied for the position at IFREMER. But at the turn of the 2000s, when I was at this commission of CNRS, I was involved in forestry and working in an agricultural research organization and I was impressed by the fact that while people in agronomy had a fairly narrow focus on French agriculture, and the foresters were quite European, the oceanographers were really working at the world’s scale. I found interesting to work on a topic that was international by nature. That was one of the things. The other thing that interested me is that the ocean is a system by itself. Having something such as the ocean where you can have different approaches, different disciplines mobilized, and a real system in front of you was something interesting. I think these were the two things that were important for me at that moment, plus the fact that this was a challenge. Now, I very much agree with what Katja was saying about the importance of the ocean and the importance of ocean science. I very often say to my colleagues that we are working at the crossroads of two common goods, science and the ocean. There is also a big challenge to educate the people about the ocean. When I was a forest ecologist or agricultural scientist, I underestimated the role of the ocean. So, understanding the importance of ocean science is something critical. Since the people do not know that much about maritime affairs and marine science, it is important to attract them so that then they become interested.

Does GEOMAR and IFREMER cooperate with respectively France and Germany?

Katja Matthes: There are lots of connections between Ifremer, GEOMAR, Kiel, and Brest. We have regular meetings between GEOMAR, the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) in Great Britain and IFREMER. And there is also the European Marine Board and the Partnership for Observation of the Global Ocean, the international frame where we exchange on a very regular basis. Kiel and Brest are twin cities. Next year, Kiel, Brest and Split will unite within a European framework called ‘Science comes to Town’ to bring the scientific values to the public, which is great. We also do joined cruises: I took part in a cruise on the German research vessel METEOR last year in the Mediterranean near Sicily, and we had two scientists from IFREMER on board. Of course, we also have different cooperations with colleagues from IRD in Marseille or CNRS. I think it is really a good time for Europe, and in particular, Germany and France, who are two big players in Europe, to come together.

Francois Houllier: It is definitely important for Ifremer to have that collaboration with GEOMAR. We collaborate with other institutions in Germany, for example with the Alfred Wegener Institute. A few years ago, I was invited in Berlin for the creation of the Deutsche Allianz für Meeresforschung, and with my colleague from the National Oceanographic Center in Southampton, we were two foreigners, all the other people were Germans. My invitation was a testimony of the good relationship that exists between France and Germany in the field of ocean science.

What is your experience on the topic of women in science?

Katja Matthes: I am the first female director of GEOMAR since it was founded in 1937, and I hope I won’t be the last. But to go back to the beginning of my career: I didn’t have any problems at first. I did my PhD in a group that was headed by the only female professor in meteorology in Germany. It was a very diverse group, with a lot of women. I then did my post-doc in the US and there were also a lot of women. I became a first-time mother in the US, which had a big impact on my life, but it was easy combining work and family there. Later, I realized there are some networks that are not so easy to be in for women. I also had the feeling that women always have to do more and work harder to take the next step. There were times when I was not so sure if I could continue – although my CV looks very straightforward.

When I went back to Germany after my postdoc in the US, I didn’t know whether I would be a professor. What helped me in this was networks and mentoring. I participated in two mentoring programs, in particular for women, to prepare for a professorship track. I had, most of the time, besides my PhD “mother”, men as mentors. They supported me and also encouraged me to apply for positions like my first full professorship in Kiel. It is very typical that women do not apply to a higher position by themselves, they tend to wait a little longer.

Later, I was asked whether I could imagine to become the director of GEOMAR. It took me a while to decide because this was a clear decision to leave science and go into management in the middle of a scientific career. At the age of 45, I was relatively young for becoming a director. This is usually not the time where you step up as a leader. I am more than happy that I did it. But being in this position, you are often the only woman in the meeting room. I felt welcomed by IFREMER and the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) and also in the international arena.

But sometimes, if I talk to people from different fields where it is less common that women are in leadership positions, they don’t expect me to be heading a global research institute. It just happened a couple of weeks ago. I know this, I smile and I take my time when I have the word. There is still a way to go before we reach equal opportunities for women.

Francois Houllier: Of course, I am not in the same situation. When I was at the beginning of my career, this was not a big issue for me. I discovered the subject of women in science when I was in charge of INRA. I remember we had a lot of women, very bright scientists, who chose to stop their career in science and move to other activities when about 40 years old. We tried to understand the reason for that and it was for me a shock, especially in areas of science like microbiology, which are very demanding, with a lot of people publishing a lot of papers. One issue that we face, for example, at Ifremer, is that we have approximately the same number of women and men. But we have less women leading labs or research units. We are trying to, for example, have more women as directors than we had in the past, but in our board of directors, we still have more men than women. We are progressing slowly, and this is not satisfactory. I clearly understand what Katja said. It happens when I was appointed as CEO and President of INRA, my former job, my predecessor was a woman, and she was quite alone in her role in France.

Are there significant differences between France and Germany in terms of support for women scientists?

Katja Matthes: We both have gender balance at the PhD level, at the post-doc level, and then there is the leaky pipeline that opens, no matter the area; François, as you said, even in the microbiology field where you have usually more women. But the postdoc phase is the time when you could start a family and it is more complicated for women to go back to work.

First, the support system is very important. And this is a big difference between Germany and France. I have a very supportive husband without whom I couldn’t have done this, but it was extremely difficult to find a kindergarten which remains open in the afternoon. Also, in France, working mothers are much more appreciated. This is very different in Germany, in particular, if you live in a small town. You are looked at, when you work in the afternoon and you are not at home with the kids.

Another aspect is the long-term perspective. If you want to have a family, then you need some perspective for your own position and maybe not change labs all the time, move with the entire family. Mobility, which is very common on a scientific career track, is not in line with having a family or settling down. And there is a lack of long-term perspectives in the German science system, even if it is slightly changing: We now have junior research groups that give perspectives for 5-6 years.

Do you take actions for women in science?

Katja Matthes: I think what is very important is role models for women in leadership positions. When I came to GEOMAR in 2012 and 2013, we funded the Women’s Executive Board. All women in leadership positions meet on a regular basis. We support early career scientists, we invented a lecture series, the Marie Tharp Lecture Series [Marie Tharp was an American geologist, cartographer and oceanographer], where we invited international role models, to really show that it is possible to have a career as a female scientist. That was a big success. At GEOMAR, just to tell you a few numbers, I am very proud that 34% of our professors are female. This is really important for me also to have strategic or decision committees and not only committees on gender and diversity that are led by women. I am definitely in favour of a quota for female leadership positions.

Francois Houllier: To give you an example, at the One Ocean Science Congress, we had a clear goal with Jean-Pierre Gattuso [CNRS research director and co-chair of the One Ocean Science Congress] to attract as many women as men. For our satisfaction, we had more participants who were women than men – 53 or 54% women. We wanted to have some diversity in the representation of the scientific community. Diversity was not only men and women; it was also geographic regions, also young versus senior scientists. We had quite a lot of early career ocean professionals or ocean scientists who were on board, I think more than 30%, so we were happy with that. But sometimes we were not that successful. For example, when we built the International Scientific Committee, this was one of our criteria to have a balanced international Scientific Committee. But at one point of time, it was complicated to balance between men and women, the geographic regions, the disciplines. But we invited five women and four men to do a keynote speech. When it came to the ambassadors, we had two men and two women. Here, again, we tried to have as much diversity as possible. We wanted to have people with different backgrounds, different perspectives, this was also very important for us.

But there is one point where we failed. At the opening session of the One Ocean Science Congress, we took a picture and there was only one woman. That single woman was our choice, she was one of the two ambassadors who was present that day, the others on the picture were officials. But in the end, the image was catastrophic for us. There were two female colleagues who played a key role in organizing all the Congress, they came to me and they said: “François, did you notice it?”. I said: “Yes, I know. It’s a pity”. It is very important to have a balanced environment: the atmosphere is much better when there is a balance between women and men in meetings.

Katja Matthes: Communication is different if there are diverse people around the table. I think it is great to make an effort, and there was clearly an effort at the One Ocean Science Congress to have women as keynote speakers. If I organize something, I also pay attention to the fact that we have equal contribution, not only gender, but also early career stage and maybe diversity if it is an international panel, just as François explained.

But it is important that scientific excellence is the guiding principle. I sometimes hear, ‘they are in the position because they are women’. Wrong: they are in this position, because they are excellent. 100 years back in the first Atlantic expedition of the meteor [The first Atlantic mission of the German survey ship Meteor began on April 16, 1925], women were not allowed on board, and now there is an equal participation of women on board of scientific research vessels and cruises. But it is a cultural change that needs to happen to have equal opportunity. And this takes time. But I feel that we are a good step ahead.

What advice would you give to young girls?

Katja Matthes: If you love science, stay motivated, and try to find mentors, and exchange, network with a lot of different people. It will not always be easy, but you will find your way with the support of a mentor and a good network.

Francois Houllier: Science is worth doing it. I think an international experience is an opportunity to travel, and build strong networks that are key in the long run. And this may be complicated, again, for women when you want to establish family, it shouldn’t become a source of precarity, but having an international experience, like Katja in the USA is very positive.

Entretien réalisé par Julie Le Gall, Noela Müller, Loïs Vaugeois, le 22 juillet 2025.

Rédaction : Julie Le Gall, Noela Müller, Loïs Vaugeois.

Mise à jour : 30 septembre 2025.