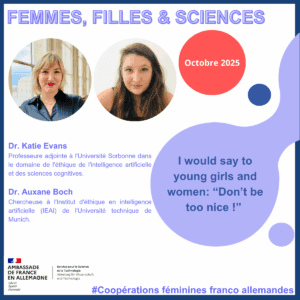

Série Femmes, filles et sciences #10 – octobre 2025

Le Service pour la science et la technologie de l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne met en lumière des femmes scientifiques et des managers de projets, en particulier des coopérations franco-allemandes scientifiques féminines, contribuant ainsi à la déclinaison par l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne de la stratégie internationale de la France pour une diplomatie féministe (2025-2030). Plus d’informations : https://de.ambafrance.org/Strategie-internationale-de-la-France-pour-une-diplomatie-feministe-2025-2030

Dr. Katie Evans is an assistant professor at Sorbonne Université in the ethics of artificial intelligence and cognitive science. She has a background in moral and political philosophy, and is a specialist in the ethics of Autonomous Vehicles. Katie is also the author of UNESCO’s graphic novel for AI literacy, and works as a consultant and expert for multiple institutions in the AI governance ecosystem. She is the chief representative of the IEEE to the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), where she serves as co-secretary for the Informal Working Group on AI under the World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations (WP.29).

Dr. Auxane Boch is a researcher at the Institute for Ethics in Artificial Intelligence (IEAI) at the Technical University of Munich. Her research focuses on the ethical and psychological impacts of interaction technologies, such as social robots and video games. She coordinates the alignAI doctoral network and co-leads the Immersive Realities working group within the TUM Think Tank. Auxane is also actively involved in science communication as an ambassador for Women in AI Germany and Women in Games.

Can you introduce yourself and your research?

Katie Evans: My name is Katie Evans. I hold a PhD in philosophy from the Sorbonne and specialize in the ethics of artificial intelligence, particularly autonomous vehicles, which was the focus of my doctoral thesis. I run my own consulting startup (Plethoria Consulting) focused on technology, ethics, and trustworthiness, and through this, I represent organizations like the IEEE in various corners of the AI ecosystem. I also serve as co-secretary for a United Nations working group in Geneva, where we handle issues related to international regulation of artificial intelligence in vehicles. I was the author of UNESCO’s graphic novel on artificial intelligence. I also teach ethics at the Sorbonne, primarily to master students in cognitive science programs, with a focus on applied ethics in technology.

Auxane Boch: My name is Auxane Boch. I am a researcher at the Institute for Ethics in Artificial Intelligence at the Technical University of Munich. I completed my PhD this summer, and my expertise lies in the intersection of psychology and technology, from interaction with video game technologies in augmented and immersive reality to social AI. I teach in various places, including the Sorbonne, as well as in Ireland. I am also a researcher and psychology lead for the Women in AI Lab and serve as an ambassador for Women in Games where I support projects linked to the Women in Games Twitch channel, including organizing streamed charity events that raise funds for different causes.

How and why did you start collaborating together?

Auxane Boch: Two and a half years ago, we organized an event at TUM where Katie was invited as a speaker. Katie was already part of the network; I had read her thesis, and we had met briefly at a conference. We have now been working together for a year. We exchange a lot together and sometimes even collaborate without realizing it, on all sorts of topics related to ethics. What is interesting is that we have two complementary approaches, and we don’t look at science in the same way. Katie is very much rooted in philosophy, with a strong background in understanding and analyzing concepts. I come from psychology, so my approach is much more descriptive and less normative.

Katie Evans: I believe that a topic like AI cannot be addressed from a single perspective: not purely from a psychological approach, a philosophical one, or even just from an engineering standpoint. It is much more valuable to test your hypotheses, your research questions, and initial ideas through discussions with researchers from other backgrounds. In our case, our collaboration is very complementary. For example, I might say that a certain technology or technological practice is morally wrong, that it is harmful from an ethical standpoint. But what is that judgment based on, as a normative researcher? Ideally, I can back it up with empirical studies and solid methodology to show not just that it causes harm, but how. That gives us a better foundation for making normative recommendations in policymaking, which is really what we are aiming for: to contribute to meaningful, evidence-based policy.

What brought you to science, to the topic of AI?

Katie Evans: I started asking myself questions about robot ethics back in 2014, when I came across a philosophical topic related to sex robots. For example, if we were to replace all sex workers with automated machines, of whatever level of sophistication, what would that do to the moral equation? Do the same ethical principles still apply? Would people have the same intuitions or moral judgments about that practice? I found it so fascinating that I realized robot ethics, which at the time was still a very niche topic, especially at the Sorbonne where I was pretty much the only one working on it, was something I really wanted to explore further. As the topic of AI became more central, other areas started emerging as well, especially in 2016 with autonomous vehicles. That led me to get funding for a PhD. It all started with this core idea: how does our normative perspective on human-machine interaction shift when we are not dealing with a person, someone with moral status or moral worth, but with a machine? It is still a fascinating question today.

Auxane Boch: My interest in AI originally came from video games. I was initially working on the psychology of video games, specifically how they shape our perceptions of the world, especially in educational contexts, what I call “social education”: for example, fighting racism, promoting tolerance, integration, and understanding of others. I wrote my master’s thesis on that topic, using a major French studio game called Detroit: Become Human, where you play as androids. Seeing how that question came up in video games, I started asking myself: how do technologies affect us morally? So I focused on cognitive, social, and moral psychology, which I first applied to video games. Then I realized we could have similar conversations around robots. That is how I got into the topic of AI and social robotics, the robot became my entry point. From there, it expanded, especially with the arrival of ChatGPT. Suddenly, the work I was doing, which some researchers had previously dismissed as irrelevant, started to be seen differently. I had been told, “Psychology doesn’t matter – what matters is the data.” But a year later, ChatGPT was everywhere, and suddenly it became important to understand how this technology affects people: how they think, how they make decisions.

Is gender a subject in your research?

Auxane Boch: I started my PhD in August 2020, and at that time, everyone was talking about bias. That was the big word; bias was the topic. People were discussing gender bias, too, but mostly all kinds of biases, often without really understanding what that meant. Still, it brought gender somewhat to the center of the conversation, even if it wasn’t directly addressed. Then, as I dug deeper and developed my thinking, I realized that the whole concept of fairness isn’t just about data; it is also about how technologies are developed and who develops them. And that is where a major problem lies: fewer than 30% of people working in AI are women or people of another gender identity beyond male, if we consider the spectrum. That has a huge influence on how technology is built, not only in terms of which data are used, but also in deciding which model to choose, what goals to pursue, and how to tune that model. A simple example we often use in Germany is the “Schufa”, the credit scoring system that determines whether you can get an apartment or a loan. Imagine this Schufa system being run by an AI. What data would it take into account? How would it decide whether someone qualifies for credit or not? If a woman hasn’t worked for six months, three different times, and she is now 50, the AI might conclude she is not a consistent worker. Whereas a human being might recognize, “Oh, those are likely maternity leaves.” If only men, or people uninterested in gender issues, are designing these systems, we inevitably end up with such problems. Right now, I am developing a research project with the Women in AI Lab on the psychological impact of technology across genders to see whether these technologies affect people differently depending on gender. And the answer is, most likely, yes. For instance, imagine I have a little social robot at home designed to help me in daily life. Will my voice, because it is higher-pitched, be better understood, or less well understood? Will the robot’s response differ depending on its own assumed gender? If I say, “I am feeling bad today,” will it respond differently to me than it would to a man? Maybe it would tell a man, “You should see a doctor,” and tell a woman, “Maybe you should have some tea and rest.” Ultimately, all of this comes back to the human behind the AI.

Katie Evans: From my side, at the heart of my research as a philosopher, I was already noticing gender differences back when I was working on autonomous vehicles and the “trolley dilemma.” The central question was: Which moral theory should apply? Most of the male philosophers working in this field were utilitarians. [Utilitarianism, in brief, is the view that what is right is what results in the greatest overall happiness for the greatest number]. And that is still largely the case today. Utilitarianism, being an incredibly rationalist and above all reductionist paradigm, tends to simplify moral complexity into something that can be easily optimized, often aligning with capitalist modes of reasoning. What I was especially noticing was a lack of diversity of paradigm. My own approach leaned more toward virtue ethics, or at the very least, I was actively questioning the dominant role of utilitarianism in everything, and I still do, to this day. Sometimes people look at me like I have three heads, simply because they are not used to seeing this paradigm questioned even though, frankly, that is exactly what a philosopher is supposed to do.

How did gender impact your experience as a woman in your fields?

Katie Evans: I think my struggle with gender plays out much more in the practical side of my work. Since I mainly work in automotive applications, there are very few women in this field. In 2016, I was in my mid-20s and was a junior researcher addressing topics that didn’t yet have the public attention they do today. Being a young woman talking about ethics was not easy. Even now, despite a further 10 years of career experience, it is still challenging to be heard and to be taken seriously. Especially considering that I am not an engineer, and I don’t have a technical background. I have worked a lot with engineers, but I am still a philosopher at the end of the day. So yes, we are clearly in the minority, and that can affect research collaborations and even policy discussions in subtle but significant ways.

Auxane Boch: Even today, in our field, there are very few women, and sometimes it is easier to work with women than men on certain topics, for example, sexual robotics. That is a subject I have studied extensively, and I have had students who worked on it as well. For instance, I had a student doing their thesis on sexual robotics, and I actually had to take action to support them in their work environment, as their colleagues were having unacceptable behaviours akin to bullying about their research topic. I think this is very problematic, especially since these are very important issues today.

Katie Evans: In my field, philosophy, there are both men and women. However, the well-known and frequently cited figures are mostly men, and you can see this at any philosophy conference. But today, it is true that women are often expected to handle the “softer” topics like ethics and societal impact, and it is true that women are much more visible in those areas. That doesn’t mean, however, that we are being listened to more. For example, if you look at some of the major think tanks in this field, the people who speak up are mostly men, even though the teams are demographically diverse. And as an ethicist, when you walk into a room full of men with whom you have to work all day on something complex, like building consensus on a particular policy, there is immediately this sense of, “Oh, okay, so she’s here to represent that kind of ‘soft’ topic, not something with teeth,” so to speak. And I really don’t like that, because ethical issues are usually at least as complex as the pure technical questions behind them, if not more so.

Auxane Boch: Psychology is sometimes seen as a “women’s thing,” but actually, it is not. The majority of current professors are men. I can think of one well-known female psychologist: Sonia Livingstone, who works on policy with the European Union, but at the same time, I can name 25 men, mostly white men from Western countries. In France, psychologists aren’t really considered scientists, which is different from Germany. Being a psychologist gives me more credibility here, whereas in France it might have taken some away. I work a lot with engineers, and they quickly realize that we can speak the same language we talk about cognitive systems together. But I have experienced multiple times not being taken seriously because I am young and a woman. I think Katie and I have developed coping behaviors to counter that. When we enter a room, we dress better, do our hair better, speak more carefully, watch our tone, laugh less, things like that. Working with women or men who are genuinely open-minded and don’t judge based on gender or age, and it does exist, is much more pleasant, and it allows us to dive much deeper into the topics.

Are you engaged for women in science ?

Katie Evans: I am not formally involved in women and science initiatives, I probably should be, and I will be. However, I do have a lot of conversations with my female students because I think I take on a somewhat “pedagogical-maternal” role. I really want to help them avoid the traps that I fell into.

Auxane Boch: I have been involved with Women in AI since 2020, and I have helped in many different areas as the organization has grown a lot. Today, this NGO is present on every continent with over 15000 members. I support women, but I have also received a lot of support from this organization. These are women working in AI, in NGOs, industry, academia, all over the world. Sometimes we call each other to discuss remarks we have received in our work that we find sexist or to share ideas that we can support together through our network. I am often invited to speak about diversity and gender, so I am lucky to have the chance to talk about these issues and educate people. I am not there to moralize, but to explain things. In my daily work at the university, I have students, and when they report things to me, I don’t hesitate to take a stand, often less diplomatically than Katie. I have been called the “academic bouncer” because I kick people out of events when they behave badly. For example, just a few months ago at an event I was managing, a guy stood up, interrupted me, and started explaining his own work even though he had nothing to do with the discussion. So, I handled him. Also, I think Katie and I have probably worked twice as hard as a number of people we have worked with. So, I teach my students to say no and to recognize when their work is theirs, so no one else can take credit for it. I teach my students that just because someone has a PhD or a professor title doesn’t mean they have any rights over you as a person.

What advice would you give to girls ?

Katie Evans: My key thing is definitely having a sense of humor both about yourself and as a kind of weapon, honestly. Because just being the smartest person doesn’t mean you’ll be listened to. But if someone challenges your expertise or legitimacy and you can counter it with a quick, witty remark you gain a little bit of power in that moment, which means next time, you likely won’t be treated the same way. But I would also say, if you have a very original idea, no one is going to like it, and there will be a lot of opposition. So, you must give up the idea that everyone is open to a paradigm shift, because that is very rarely the case. And the more you work with people from different backgrounds, academically speaking, the more likely it is to get stuck in this way. So you really have to aim to be able to explain the core of your idea to everyone. You have to know how to express yourself well and explain clearly. And another piece of advice: don’t be too nice. People will ask you for help because you are a woman, and maybe that is a stereotype we have, that women are expected to want to help. Don’t help too much. You can be kind and cordial and try to support others’ research, but you don’t have to be overly helpful. That is something I learned the hard way.

Auxane Boch: I think there is this widespread mindset that if you do this kind of work, if you study these fields, then you can’t have ideas that go beyond the framework you started with. I think the strength that Katie and I have is that we are very interdisciplinary, and because of that have ideas that go beyond the silo we are in. And if you have an idea, you have to believe that it might be a good idea, but it is also okay if it is a bad idea, and in any case, it is worth trying. So, a second piece of advice is that failure is part of success. I think everyone knows this, but it is really important to embrace failure. I come from experimental psychology, so failing already means finding something; it means finding out that something wasn’t right. And that is super important. Then, being a woman means you have to be a little stronger than others. Unfortunately, in our field, which is still largely male-dominated, you need to have a bit more of a strong character and not let people walk all over you. Humor works really well for that, that is definitely true.

Entretien réalisé par Julie Le Gall, Noela Müller, le 07 octobre 2025.

Rédaction : Noela Müller.

Mise à jour : 30 octobre 2025.