Série Femmes, filles et sciences #6 – août 25

Le Service pour la science et la technologie de l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne met en lumière des femmes scientifiques et des managers de projets, en particulier des coopérations franco-allemandes scientifiques féminines, contribuant ainsi à la déclinaison par l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne de la stratégie internationale de la France pour une diplomatie féministe (2025-2030). Plus d’informations : https://de.ambafrance.org/Strategie-internationale-de-la-France-pour-une-diplomatie-feministe-2025-2030

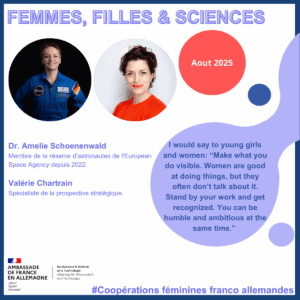

Amelie Schoenenwald est membre de la réserve d’astronautes de l’European Space Agency (https://www.esa.int/) depuis novembre 2022. En octobre 2024, elle a commencé le premier des trois programmes de formation de la réserve d’astronautes, chacun d’une durée de deux mois, au Centre européen des astronautes de l’ESA à Cologne, en Allemagne.

Valérie Chartrain est spécialiste de la prospective stratégique, qui a travaillé en coopération avec le Centre national d’études spatiales (CNES) sur des questions liées à l’espace. Elle possède également une expertise reconnue dans les spiritueux distillés ainsi que dans l’art contemporain.

Elles ont ensemble participé à l’évènement Space Embassy organisé par l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne.

Can you introduce yourself?

Amelie Schoenenwald: I am a German reserve astronaut at the European Space Agency. But actually, my roots are somewhere else. I am a scientist, and I studied biotechnology and biochemistry at the Technical University of Munich, and I earned a PhD in Integrative Structural Biology after I did a couple of research stays abroad in Israel, Austria, and Singapore, and the United States. At the moment, I work as a full-time project manager in the pharmaceutical industry. I also participate in astronaut reserve trainings: every year, I have two months’ trainings, and this will prepare me for a potential future mission as an astronaut.

Valérie Chartrain: My path, as far as I am concerned, wasn’t completely planned. It is made of shift and turns, but I am glad about it. I started with literature, moved to political science, and later to sociology to end up working in contemporary art. Working in contemporary art means leading galleries and I started a feminist magazine. Art helped me really develop curiosity. After a few years I started working in the spirits industry. And after questioning what was making sense in the world of spirits, I started thinking about what would make sense tomorrow. The future became my research so I moved towards strategic foresight, which is what I am doing now. I am a strategist in foresight, which means that I spend most of my time researching the future or at least possible futures, not only to predict, but to imagine, to map out, to build new narratives that we can use now to help better decision making, and also to help institutions and organizations to work with uncertainty.

Could you explain what your day-to-day life looks like?

Valérie Chartrain: In my day-to-day life, I spend a lot of time reading, meeting people, making connections, which is the way I do research. I am looking at different signals, a lot of serendipity. Then I work on organizing and structuring questions that I am asked. For example, on space, I was asked: what if we are a French and German team on the moon and we start mining the moon? My work is how can I structure the thinking process so then we can actually come up with relevant positioning at the end of the process.

Amelie Schoenenwald: For me, it is a bit different because I have these different worlds I live in and different roles I play in my life. On the one hand, I just live a very, as you said Valérie, down-to-earth life, very normal. I go to work; I learn a lot of new things. In my job, I deal with a lot of strategic projects which are usually on a very high level, and it is really interesting because I get in touch with a lot of different people. But then, on the other hand, I have this parallel universe I act in. Sometimes during the year, like these two months per year where I go into the astronaut reserve training, I live in a completely different world. I live in Cologne where the European Astronaut Center is. I get to train, to live and work with my fellow reserve astronauts. It is just absolutely amazing to get there and get all this inspiration for my normal work. My big dream in the end is to find more and more synergies to bring these two worlds together.

Where does your interest for space come from?

Valérie Chartrain: I think space came through meeting people, being curious and being open. And the way also I move from one career to the other, this is not that all of a sudden. This came always very gradually through learning something new, through having a different crowd of people around me, that bring me somewhere else. At some point, I started to work mostly in strategic foresight and tried to educate myself. I had the first education in Germany, and then I thought it would be interesting to see how it is done in France, and there I met different people, from CNES (Centre national d’études spatiales), and they started asking me questions and we started working on different projects together.

Amelie Schoenenwald: For me, the red thread throughout everything was science. When I was a kid, I just really loved nature, and I wanted to learn everything about it. I was super curious. In the end, I decided to study biotechnology and biochemistry because it is the very core of what nature consists of. But I was also going onto this path because every night I saw the stars. When I was lying in my bed, I saw the universe, and I was asking so many questions that nobody could answer. This took me into the scientific path. But there was no chance to become an astronaut at that time because I was too young to apply. I didn’t even know that you have to apply or that you can apply. So, I started as a scientist and I was working in laboratories. I was doing my own experiments and spent many years doing basic research. Then I moved to a different side of science, the managing side of science and bringing pharmaceuticals into the market. Then once the chance came in 2021 that I could apply to become an astronaut, it was just the first revelation. This is actually not just science fiction: it is real. You can become an astronaut. I was extremely lucky that this call to apply came for me at the very right moment in my life because I got all the scientific qualifications and was in the right age. I did everything I needed to do to apply, and I was just extremely lucky.

Working in space is going back to my roots, back to the basic science part where we do experiments and try to do something that will benefit all humankind on Earth. Space also incorporates all other perspectives of science. You have engineering, you have materials sciences, you have medicine, physiology, biology, physics, and so forth. And all these telecommunication aspects with media and satellites and climate change. There is everything included in space. It is not going further down into a corner, a specific area of science, and be a very specialist in this one. It is actually opening up to a whole new perspective.

Valérie Chartrain: There is something that Amélie said, which I think is actually very important, and I think people are often not aware of it. I am saying this as someone who is not coming from hard science. I realized how broad space is and how unaware we are of the impact of space on our daily life and how there are actually opportunity for all sciences. When one thinks about space, one think immediately: engineer. But it is much broader than that.

How gender did impact your experience as a woman in your fields?

Valérie Chartrain: The fact that I am a woman impacted my decisions in my life. I grew up with a lot of brothers, male cousins, so in a very male environment. Actually I couldn’t always do the same things as them. I remember that as a kid I wanted to become a karting champion. I remember my family saying: but that is not for a girl. I didn’t really understand why it was not for a girl. What was the problem with me? I think that this sense of injustice really shaped how I saw the world, and shaped my decision to study politics, to study sociology. I think that explains also why I have always been into civic or associative engagement. And it still has an impact today in the way I am going to do my research and organize the different thinking process. What was always shown to me as being knowledge, universal and natural knowledge, actually was always a very male point of view. There is no real universal knowledge, and there is no such thing as neutral. So, I feel like the impact it has on me is that I have to stay alert to what is presented as being evident, maybe is not evident.

Amelie Schoenenwald: I think this gender discussion, the fact that I have a gender, is something quiet because it is always present. It is a constant thread throughout my journey. Sometimes it is invisible and sometimes it is unmistakably present. When I went through different stages of my life, in academia or any sport or a free time activity I have done, diving or motor biking or any expedition, I often found myself being the only woman present. That is okay, but what I found is, specifically in leadership discussions or if there is any high-level research collaboration or something that is going to a different level, again, it is not that you are openly discriminated, but it is just subtle things: you are interrupted more often, you have ideas that are overlooked until somebody else repeats them, or you are asked to organize instead of leading things. It is just these small moments that erode confidence in many women, and it is very tough to stand firm, to speak up, and really believe and put gravitas in the words you are using.

Now, in my current job, in the pharmaceutical industry, it is similar but yet with different challenges. Sometimes you have your authority questioned more than your male counterparts, or you have to work harder to be taken seriously. But of course, again, it is very subtle. There are some coping mechanisms that I think women adopted over time. It is either being louder, clearer, more empathetic, or even just working harder. But in my position at ESA as a reserve astronaut, I am super proud of how far I have come as a person, and how far we have come as a society, because right in my astronaut class, there is almost half women. We have been selected, we are represented, we are respected, we are visible, and especially in a very historically male-dominated field. I see this as a huge chance, opportunity, but also responsibility to be excellent, not only to prove myself, but to be out there as someone who is watched by everyone, but especially girls who are imagining their own future in science, in engineering, and beyond. This is something that I’m proud of, but I am also aware it is a huge responsibility.

Did you have a mentor, or benefited from mentoring programs?

Amelie Schoenenwald: I wish I could say that there was a range of women mentors, but unfortunately not. I think I have my own way of doing things and it is very tough to find an example who did exactly the same that could have helped me here. I think there is always something to be respected in every single person around you. I just try to pick and match whatever fits into my own personal mosaic of life.

Valérie Chartrain: As far as mentors go, I can’t really say I had one at least not in the traditional sense. But along the way, I was lucky to cross paths with men who acted as allies. They offered me a hand, gave me a chance, or opened a door. That started early on, with teachers. While I can’t name a female mentor who directly guided me, I’ve drawn immense strength and clarity from the words of women who came before me. Writers or activists like Simone de Beauvoir, Gisèle Halimi, Flora Tristan, Donna Haraway, Angela Davis, they shaped the way I understand the world and my place within it. They mentored me through their books, their convictions, their courage. And now, I feel it is my turn to give something back. I am still figuring out what that looks like, how to share, how to support, how to pass something on.

Do you advocate for women in research, in science?

Amelie Schoenenwald: I strongly believe that the most powerful moment is not when you are the only woman in the room, but when it is no longer an exception. I am particularly thinking about one example from yesterday. There was a conversation here, and it was three men and me speaking, and it was about holiday planning. All three men were saying they have no say in the holiday planning: “It’s the boss at home who does that”. They make the money, they pay for the holiday, but the organizing, the women can do it. I think in these moments, you have to speak up and challenge this historical way of thinking that this is a woman’s job to do things like that.

Apart from speaking up, I think there is another thing that I can do in my role at the moment, and I hope that I can do much more in the future. When I go on stage just by being me, by being authentic, I realize there are many more girls and women raising their hands to ask questions just because it is me on stage, because it is more relatable. This is just the first step to make it more normal to have women in high-visibility positions. It is a long journey. But beyond that, I think the allyship is the third part. Having men as allies, that is absolutely crucial. It is even more crucial to have each other as women as allies, because sometimes we are our own enemies. I think we need to overcome this because otherwise, there won’t be any change. We need men as allies. We need women as allies. We need to be standing next to each other and support each other.

Valérie Chartrain: From the position I am now, I don’t think I can really act on women in science issues. But what I can do is to make sure that when I am working on a project, women are part of the discussion and also everyone that is put aside and the younger generations. There are many sciences where you have way too many women. In gender studies, you have only women. So that is also a problem: it is not only about where you don’t see women, but also where you see not enough men. And the fact of not having all these different voices in a room has actual consequences.

Amelie Schoenenwald: I love what you said, Valérie, it is just about having different perspectives on the table, whether it be, I don’t know, religions, generations, but also, thinking from a business context, different functions in a company. If you try to make a strategy that impacts some functions or people in society, it is actually quite advisable to include them in the decision-making process. I also think young generation are important, it is the most important action. If you are injected with a different role when you are very young, it is very hard to get rid of it later on in your life. It shapes your whole perception of what life is supposed to be like or how you are expected to behave in society.

Did you notice difference between France and Germany in terms of women in science?

Valérie Chartrain: I don’t see so many differences, in terms of women in science between France and Germany. I can see cultural differences of course. Except these little details, I feel like from a more political point of view, the diagnostics are the same, the political discourses are the same around this, the willingness to have more women in science, even at the European level. I think it would be more powerful if France and Germany start to tackle that together instead of having everyone doing things in one corner.

Amelie Schoenenwald: Allyship is super important, cross-gender, but also now across borders. When I think of the conversations I have had with French people, someone who was raised in a French-speaking environment as well, I noticed there are cultural differences that I wasn’t aware of. And you gain perspective on the German culture: that’s the way we do it, but why are we doing it this way? We can all learn from each other.

What advice would you give to girls and young women?

Valérie Chartrain: Be strategic. There are actually a lot of structures, networks, funding. It is about being smart, know how to use them. And make what you do visible because I feel that often, women are good at doing things, but they don’t talk about it. I am not talking about developing a crazy ego, but it is about just standing by your work and getting recognized. You can be humble and ambitious at the same time.

Amelie Schoenenwald: In very short, stay curious and just go for it. But I think what we really need to learn as women is this networking aspect. You have to think about what you want to do, and then you find something that you think you like a little bit, and then you just go for it. I think it is super important in the very early steps that you find somebody you can bounce ideas off with, who gives you an insight. There is so much support, it is up to you if you want to know about it because you need to research, find it, and actually apply or whatever you can do to get into these networks. Also myself, I didn’t do it enough back in the time. So do your research, get input, get perspective from people who are more experienced, and then you decide and follow through.

Rédaction : Noela Müller, Maxen Owens, Julie Le Gall, SST Berlin

Mise à jour : 29 août 2025