I want to tell girls : « Don’t behave like a man! Pressuring on carriers, suppressing emotions or avoiding empathy shouldn’t be the key to success. »

Série Femmes, filles et sciences

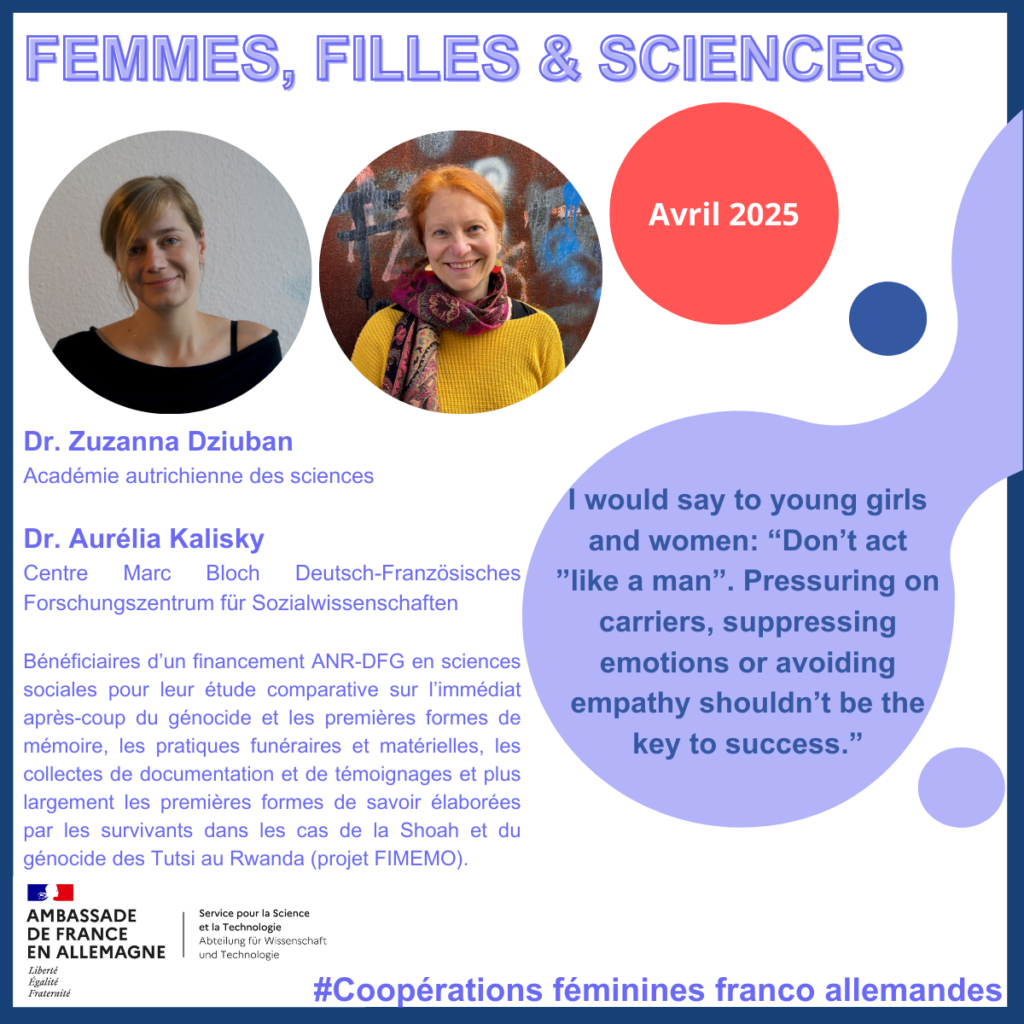

Entretien avec Aurélia Kalisky et Zuzanna Dziuban.

Le Service pour la science et la technologie de l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne met en lumière des femmes scientifiques et des managers de projets, en particulier des coopérations franco-allemandes scientifiques féminines, contribuant ainsi à la déclinaison par l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne de la stratégie internationale de la France pour une diplomatie féministe (2025-2030). Plus d’informations : https://de.ambafrance.org/Strategie-internationale-de-la-France-pour-une-diplomatie-feministe-2025-2030

Deux chercheuses, Dr. Aurélia Kalisky du Centre Marc Bloch Deutsch-Französisches Forschungszentrum für Sozialwissenschaften, et Dr. Zuzanna Dziuban de l’Académie Autrichienne des sciences, ont répondu à nos questions.

Aurélia Kalisky et Zuzanna Dziuban bénéficient d’un financement ANR-DFG en sciences sociales (https://anr.fr/fr/detail/call/appel-a-projets-franco-allemand-en-sciences-humaines-et-sociales-fral-2024/) pour leur projet FIMEMO, une étude comparative sur l’immédiat après-coup du génocide et les premières formes de mémoire, les pratiques funéraires et matérielles, les collectes de documentation et de témoignages et plus largement les premières formes de savoir élaborées par les survivants dans les cas de la Shoah et du génocide des Tutsi au Rwanda.

Can you introduce yourself, your studies and your research?

Aurélia Kalisky: I was born in Paris and studied comparative literature in Paris. I started my career in France, but I also worked in the context of an international scholarly association on crimes against humanity and genocide called AIRCRIGE, trying to bring together universities and also activists and NGOs. I did that for a couple of years and then I decided to do my PhD. After working a lot on big projects, also in France, and writing a book about children during the Holocaust, I got a scholarship to do my PhD in Germany. I already loved Berlin and decided to move there. I had my two children there and started my career in this German context, which is very different from the French one, because it is accompanied by precariousness, although you have more freedom on other levels. I specialised more and more in what you could call comparative genocide studies, with a focus on forms of testimony and testimonial literature. As a literary scholar, I have also been concerned with historiography and the epistemology of the human and social sciences in relation to genocides and crimes against humanity, and more generally to extreme political violence. I am mainly based at the Marc Bloch German-French Research Centre for the Social Sciences in Berlin, but before that I worked for a long time at the Leibniz Centre for Literary and Cultural Research (ZfL) in Berlin.

Zuzanna Dziuban: To complicate the situation a bit, I am nether German nor French but Polish. I studied philosophy and Culture Studies in Poznan and did my PhD in Poland in 2009. Only afterwards, I moved to Germany to work on some postdoctoral projects and, finally, ended up in Berlin. I had started working on the material, affective, and political afterlives of the former extermination camps in Poland, the Action Reinhardt camps, shortly after my PhD. When I was doing research on those sites, I became fascinated by archeological projects that were conducted at the sites in the late 2000s and I followed those developments. I have been particularly interested in the forensic aspects related to the Holocaust and the material trajectories of the former camps. Also, my trajectory is about the academic precarity to a certain extent. Since I moved to Germany, I was forced to travel a lot across Europe, following jobs or research projects in which I was offered positions. I worked at the University of Konstanz, spent a year at the Wiesenthal Institute in Vienna, three years at the University of Amsterdam, at the School of Heritage and Material Culture. For the last five years, almost six, I have been based at the Institute of Culture Studies of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, working in a project Globalized Memorial Museums, which is also a comparative take on political violence and on engagements with political violence, but in the context of memorial museums. Now, I am moving back to Berlin to carry out this project at the Center for Antisemitism Research at the TU Berlin.

Zuzanna Dziuban: We met with Aurélia in 2017. We were in her apartment together with a group of other activists from the collective “Ciocia Basia”, in German “Tante Barbara”, which was established in 2014, in Berlin, to support people from Poland in accessing abortion in Germany. It was a context of activist work on access to reproductive rights and the reproductive justice that initially brought us together, the joint research was to follow later.

Can you can introduce to us the project FIMEMO, on which you are both working together, and for which you received an ANR-DFG funding?

Aurélia Kalisky: I already received an ANR-DFG in 2017 for three years, which was already on the same topic, but focused exclusively on the Holocaust. I did it together with Judith Lindenberg and later with Judith Lyon-Caen, both French historians working on the historiography of the Holocaust. Zuzanna and I were already familiar with each other’s work, and I knew that she was working with someone on Rwanda. I had long had the idea of extending my first ANR-DFG project to a comparative level and to include another genocide, the genocide against the Tutsi, in order to look at the same phenomena and to try to reflect more generally on the aftermath of genocides and on the production of knowledge and the first forms of memory by the people who have lived through this experience.

Zuzanna Dziuban: When we started speaking about the project and the potential of comparative approach between the aftermaths of the Holocaust and genocide in Rwanda, one aspect came forward as new and a phenomenon that was, in fact, never researched in the context of the Holocaust. It pertained to material practices of survivors. I am speaking about the processes of the knowledge and memory production, which accompanied the practices of searching for bodies, of exhumations and reburials. Only recently, inspired by Eric Sibomana’s work on Rwanda, I discovered that Jewish survivors performed hundreds of exhumations in Poland and that those practices have not been researched to date, and have not been seen as a form of survivor-activism in the first decades after the Holocaust. We realized with Aurélia that a lot of research done in the last decade on the early aftermath of the Holocaust did not include those practices, and that they are totally fascinating. They were fascinating also because they went against the dominant politics at the time, especially in Poland. The survivors were not supported by the state, and had to perform those exhumations and reburials on their own.

Is gender a topic that you study?

Aurélia Kalisky: I would say that, as always in history, women are almost completely invisible, and this is especially true in the context of Holocaust history and remembrance. Of course, there are a few important names, but for the most part the work of women is completely invisible, even though they played a very important role in the first initiatives: they collected testimonies and were very active in all the care and education work, for example. In Rwanda, this is a very important dimension because there are many more women and girls who have survived because the genocide was even more deadly for young boys and men. The women, on the other hand, were subjected to very cruel forms of sexual violence and were exposed to AIDS, so their voices are very specific. In Holocaust studies, we are still trying to complete this incomplete narrative of the gender dimension. At the same time, we will also reach a limit, because we are confronted with a material impossibility to reconstruct what was said, what was sung, what was performed or taught by these women, who were much more in charge of all the ritualised aspects in Rwanda and also in the post-Holocaust context.

Zuzanna Dziuban: It is also about bringing them back to visibility. For instance, very often the assumption persists that this physical material work of exhumations was performed only and exclusively by men, which is not true. In many contexts, the care for the dead was initiated and carried out by a woman. A gender aspect is also visible in the ways in which different perspectives and modalities of writing of history have been developed recently by women scholars. Their sensitivities bring into the picture aspects and problems that were not traditionally included in the writings on the genocide. The emotional aspects, affective aspects, the ways of coping with trauma, for example, are brought by women scholars into the picture and allow for a totally different way of narrating of the history of the aftermath, and for different forms of analysis.

Has gender impacted your experience as women in science?

Aurélia Kalisky: I felt at times a form of institutional violence. As a woman and as a mother, and in very difficult moments of my life, I had often the feeling that it was much more difficult for me than it would have been for a man. The German society is very hard on mothers, especially when you want to start to work again quite rapidly while balancing work and motherhood. It is then a decision to work only with people that have the same political agenda, the same sensitivity and also to work with engaged women. For me, it became more and more important.

Zuzanna Dziuban: I also realized that working in contexts where I write with other women and function in scholarly communities, in which women dominate, is a much safer and much more comfortable, and, therefore, more creative work environment. It is also the case because, in those spaces, we give ourselves permission to speak about emotional dimensions of this work, which I think are still often a taboo in the male dominated academia. We should not, and cannot, deny the emotional impact of this work, so I will always seek a space in which this can be addressed, because otherwise, the work on those topics can become too difficult, too overwhelming, too damaging. Also, one of the reasons why I left Poland for Germany was that I couldn’t cope with the gendered hierarchies constructing work at the academia. I hoped that it would be different in Germany or in Austria: maybe it is, a little bit, but it continues to be disappointing how this gendered system is perpetuated. It translates into who gets positions, what performance is expected, and what advice women give to each other. The advice to how to handle the academic system and be successful is often “behave like a man”. It still functions as a legitimate guidance, I heard that in Germany several times.

Aurélia Kalisky: Yes, you can see that we are still from a generation where the women who are in top positions only arrive there at the cost of not expressing any emotion or any empathy and behaving like a man. And I was also told that often.

Zuzanna Dziuban: When it comes to another gendered aspect, I don’t have children, and it is also my decision and my partners. But I can totally understand why this decision could be considered a result of the precarity at the academia. Over the last 10 or 12 years, I had to move at least six times to follow the jobs or to have a stable financial and work situations. I can imagine that this is something that affects many people’s decision to have a family, to have children. And of course, this hits women harder than men.

Aurélia Kalisky: Yes, and for me it is exactly the opposite. I had to refuse some career offers because it implied moving, and it was not possible to move with two children and a partner working in Berlin.

Zuzanna Dziuba: Definitely, the academic precarity, the trouble at the job market, the fact that getting a permanent position is like a dream never coming true, affects our positionalities, our life choices, and sometimes hurts our life choices and our relationships heavily.

Aurélia Kalisky: But I also think that the institution is so rigid and so hierarchical and pushing so much the notion of career, of ego, and of ambition that this is, paradoxically, what made me prefer precarity also. Because the precarity within these projects where you are choosing your partners, to have this very good relationships within the work, for me, it is essential. Not that the precarity is not another form of violence. Of course, it is too. But at least you are doing your thing and you are dealing with the relationships as you want to.

What advice would you give to girls and young women that have an interest for science?

Aurélia Kalisky: What I am experiencing right now in the activist context is that this generation has a lot more to teach me. I think they are so great! They are experiencing the same fears, but they are facing them with much more solidarity, including among their male comrades, and they also have this sense of urgency because of the gigantic backlash and authoritarian drift we are experiencing, against the catastrophic backdrop of the climate crisis and crimes against humanity being committed in plain sight. All this is so urgent for them – and rightly so! – that I feel I have much more to learn from them than I have to teach them.

Zuzanna Dziuban: Don’t behave like a man! I would also say that it is important to be kind to one another, especially to your peers, and organize in collectives or groups or share your research. Don’t drift into a lonely path, but try to find safe spaces in those hierarchical, violent environments. Also, don’t allow the institution to force you to deny any important parts of you that are invested in your research. Maybe because I am a cultural studies scholar, it is obvious for me that the political positioning has to be part, if not at the heart, of what we are doing as academics. Yet, we are very often forced to deny or silence or not to address our positionalities or the political stakes of our work because then we are accused of not being objective or nuanced. I think objectivity is a way of killing nuance, and not the other way around.

Entretien réalisé en anglais le 07 mars 2025 par Julie LE GALL et Noela MULLER,

du Service pour la Science et la Technologie de l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne.